Dead grandmothers no more: the equal accommodation classroom

Let me tell two anecdotes to put the Dead Grandmother Syndrome in perspective.

I remember when I was a student in Evolutionary Biology in my junior year of college. Right before the midterm, I got really sick with the flu. I felt like hell and doing normal things seemed like a physical impossibility. If I took the miderm, I would have gotten a horrible score, only because I was so darn sick.

So I called my professor the day before the exam, then at his request I dragged myself out of my (on-campus dorm) bed to his office explain how I was sick with the flu. He sized me up and said that I would have to take the exam tomorrow, even though the flu was going to stay bad for another couple days. He said that the only way I could get a reprieve from the exam would be to get a doctor’s note, from any doctor’s office off campus. He said that this was his policy, and it would be unfair to offer an exception to me just because I looked sick. (He didn’t seem to entertain the notion that the policy itself was unfair.) He required an off-campus doctor’s note because the health center on campus was notoriously specious and would give a note for pretty much everything. (And every woman I ever talked to who walked through the door had to take a pregnancy test. Not kidding.)

So, because I was sick and because my professor didn’t trust the legitimately untrustworthy campus health center, I had two choices:

Take an exam through physical misery and probably perform horribly on it.

Find my way to an off-campus medical office, find the money for the visit (I only had catastrophic coverage at the time), just to get a note verifying that I so obviously have a bad case of the flu.

I found both options to be miserable, but I chose #2 because I thought that my grade was important. I got someone willing to be in a car with me to drive me to a doctor, then wait while I paid for my “Yes, he has the flu. What are you, blind?” note. I brought the note to my professor’s office, and he accepted the note and rescheduled the exam for the following week.

This happened about 22 years ago. But the memory is seared into my memory because I was so upset at the fact that the professor didn’t believe me — or had a policy in which all students are not to be believed. It was a dumb policy that made being ill even more miserable. I felt disrespected.

Here is my second anecdote, from just last year. Right before exam season, a close member of my family died. At the same time, I was chairing a search committee and the candidates were visiting campus.

At this tough moment, the members of my department came through big time. My students were very understanding about how I shifted priorities temporarily. I am grateful for everyone’s understanding.

Nobody asked to see a death certificate, or a funeral program, or an announcement in the paper. I doubt anybody sniggered behind my back that I invented this death to buy more time to fulfill my job duties. I would have been been outraged by such behavior.

Nonetheless, that is the reality for many of our students who have the misfortune of experiencing a tragedy during the middle of the semester.

I wouldn’t dare suggest to anybody that their personal catastrophes may have been invented. The risk of a suggested accusation or doubt outweighs the cost of accommodating the willful deceivers.

Of course, the proportion of students that are willing to be deceptive are fully prepared to take advantage of this level of civility.

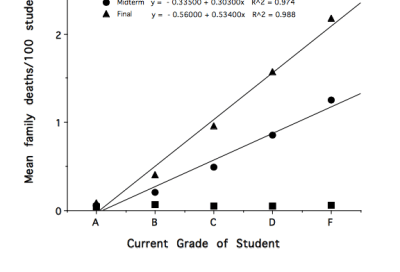

From Adams, M. 1999. The Dead Grandmother/Exam Syndrome. Annals of Improbable Research 5(6): 3-6.

Clearly, students who have deaths in the family don’t mention it unless an exam is coming up, because it has little bearing on the outcome of the course. There are two possible — and non-exclusive — explanations for the positive association of grades and reported deaths that Adams reportedly found in his students.

The first explanation, which you’ve probably heard a lot, is that students are more likely to invent a grandparental death if they’re doing poorly in class.

The second explanation is that students who are doing just fine in class may experience the same rate of grandparental deaths as those who are earning poor grades, and the students who are doing well are less likely to mention their personal circumstances. However, students who are on the margin of not receiving a desired grade are more likely to mention unfortunate personal circumstances that might interfere with their ability or availability to complete assignments and prepare for exams.

Students don’t necessarily like to share personal details with their professors. They are embarrassed when they cry in our offices, and would probably prefer to not have to reveal that they are experiencing personal sorrow or unplanned travel for family circumstances. There is a power differential between professors and students, and requiring students to reveal how much personal suffering is caused by family matters is a creepy enhancement of that power differential, like how Hannibal Lecter revels in his power over Clarice Starling.

Of course I know that some students make up fake reasons to get out of, or reschedule, exams. And I’m so focused on fairness, that I am quite opposed to letting anybody profit from their own willingness to be deceptive.

I never want to be in a position to adjudicate the validity of an excuse. I don’t want to decide whose personal circumstances are valid interruptions of academic work and those are not valid. That would also be unfair.

I design my classes so that I don’t have to even hear about any dead grandparents or demand notes from doctors or coaches.

How do I do that? I build flexibility into the grading system so that everybody can miss something here or there without having to provide an excuse or evidence.

I drop the score of the lowest exam, even if it’s a zero. I accept late assignments from everybody, and the penalty for being late steadily grows in a way that doesn’t really hurt those who are only slightly late. I drop the lowest score for in-class assignments and quizzes, even if it’s a zero.

There are lots of benefits to policies with this kind of flexibility. I don’t have to administer makeup exams. I don’t need to create special rules for student athletes. Students don’t have to prostrate themselves before me with stories of personal grief, nor invent an excuse for a long skiing weekend. I don’t have to keep track of or excuse absences, even if we’re having a quiz. Students who miss class are treated equally, whether they were at a funeral or an amusement park, if they overslept or had a car accident, if they had a sick kid or if their boss asked them to work extra hours. They don’t need to explain, and they all get the same amount of leeway.

With my policies, those who don’t need some slack still receive it. However, I do think that students with more challenging personal circumstances win out more under this policy and students who have been putting in an earnest effort all semester won’t suffer the consequences of having a few bad days.

As you’re putting together your syllabus for this spring, what do you think about cutting excused absences and makeup exams, and instead building policies that build in flexibility for everybody?