Honing a skill that all scientists need

To learn how to distill complex topics into direct communication, we can look beyond science for role models.

You know what a lot of scientists are bad at? Taking a complex situation and then developing the perspective and rhetoric to break it down to the most critical points in just a few words. A lot of us like to think that the complexities and subtleties are always important, that the detail in science is what makes things matter.

However, a digestion and distillation of all the complexities into the most critical and simple pieces is as important in science as it is in other fields.

I remember having a discussion, something resembling an argument, at the dining hall at the field station. Someone was peeved that a journal editor required a “tweetable abstract” that communicated the main point of their manuscript. My dining buddy said that it was not only impossible, but perhaps a little insulting to their work, that their work could somehow be represented so briefly. I don’t like to force arguments but felt compelled to disagree, that if they consider their work to be valuable or important in some way, even in a deep niche of science, they should be able to find a way to explain how their work matters in a few words.

While I recognize this is important, I don’t feel that I’m particularly good at it. I’ve struggled with putting together an elevator speech, because my interests have been wide-ranging and I work on a variety of questions. If you’re a regular reader here, you must appreciate the fact that I sometimes dance around an idea for lack of the ability to just come out with the best single statement that really puts the pin on the target?

Even though a lot of us are bad at communicating in extremely direct snippets that get to the heart of the matter, I think the most successful scientists are experts of this craft. That’s because being this is critical for fundable grant proposals, and also having your ideas catch on beyond have your immediate peers. For example, think of the folks who do TED talks, get selected as MacArthur fellows, regularly serve as sources for journalists, etc. They are able to distill out the message in a very clear manner. That’s valuable.

It’s easier to do this in writing, because you have the opportunity to revise, and revise, and revise. Ideas take shape in the process of writing. What I aspire to is being able to see the world with enough clarity and vision that I can think on my feet and communicate as well in unscripted conversation. I realize that this kind of wisdom in communication comes from deep thought and experience. What really blows me a way is seeing this kind of thing in real time.

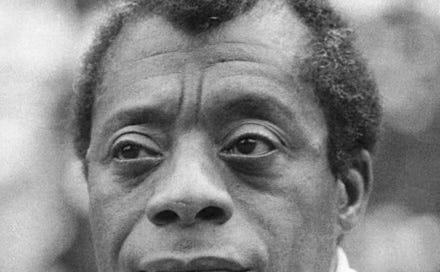

Who do I think of who are masters at this craft? There are some scientists, but the people who I’ve seen do this better than anybody else are in other realms. Two folks come to mind

The first one is James Baldwin. (In addition to the clarity and force of his message in writing, his prose is just gorgeous.) What I find super impressive about James Baldwin is how he communicated in unscripted interviews. The documentary about him, I Am Not Your Negro, features him in a variety of conversations. In the face of questions about incredibly detailed and challenging topics, Baldwin focused conversation on the central points that really matter, in a way that didn’t dismiss all the tiny details, but instead, zoomed out to the larger picture that puts all of the little details into perspective.

The other person who regularly floors me with his distillation of ideas is US Secretary of Transportation, Pete Buttigieg. He’s a master of entering in conversations that are designed to rhetorically trap him with falsehoods and false equivalencies. But time and again, he emerges from these conversations having forcefully made his point with absolute clarity in an environment.

I wish I could think that clearly on the spot about as these guys about my science, or for that matter, about anything.

We are doing research on things that we think are important. Why else would be spending so much time and giving so much of ourselves to this career path? I think it’s a career and not a vocation or a calling, but nonetheless, we’re investing ourselves into what we do because we believe in it. Then, shouldn’t we be able to be engaged with conversation about folks and explain what we do and why it matters?

When someone asks me about the science I do, I’d think it’s important for me to be able to explain in a couple sentences what it is and why it matters to people who are paying (taxes) for me to do this work. When I’m teaching about climate science to non-majors, I think it’s critical to communicate what is happening, and how there’s ample hope for a good future, and be clear and convincing.

Understanding these things in our own minds is one thing, but putting having the scientific (and moral) clarity to make it obvious to those who we are talking to? That’s seems to be a rhetorical gift, but I’m still going to keep practicing.

Science for Everyone is sponsored by SciSpace. Unlock 40% off annual or 20% off monthly SciSpace subscriptions with codes TER40 and TER20—try it today!

I have been adopting Randy's Olsen's ABT approach a lot more lately in teaching clarity, logic and purpose to my students. And, But, Therefore - And provides the background and context, but introduces the conflict and Therefore provides the resolution. Works for all sort of things.

Some folks are just naturally gifted at this. I wish I was! But one thing I like to do is to always think of an analogy to explain a concept. That certainly helps to get a message across in a common currency.