How strobe ants do the strobe run

It’s been a while since I posted about some of the science I’ve been doing, so here’s a fun natural history story for a change.

If you have the fortune of being in the northern end of Australia, you’ll find some ants at your feet that appear to be under a strobe light, paradoxically in the light of day. These gorgeous ants (see above) are colloquially known as strobe ants (genus Opisthopsis). They’re remarkably common, and definitely catch your eye.

I dug into the literature to learn what we know about Opisthopsis. The answer is shockingly little. For such an obvious and cool ant, there’s been essentially no work on its biology that we could find in the literature. They’re a blank slate, at least since William Morton Wheeler wrote about them one century ago.

I was going to spend some days in Darwin (orienting students for a half-year research experience, thanks to the generous support of the National Science Foundation) and I had a few days to knock out a quick project. I thought it would be fun to ask: How do strobe ants strobe? It really looks like they’re jumping as much as running, like a jumping spider. I knew when collected in ethanol, their legs broke off very easily, far more than other ants. What’s going with their leg musculature?

I was going to take a bit of time to film some strobe ants. The problem is, they’re so fast, if you just watch them or use regular video, it’s just a blur, because they’re so darn fast. I did some homework into borrowing or renting a high speed camera while I was up in Darwin. It turns out this would have been absurdly inconvenient and very expensive. While asking folks about high speed videography on twitter, it was pointed out that the slo-mo function on recent iPhones would record 240 frames per second. Some back-of-the-envelope math with my colleague James Waters suggested that would be just enough to catch how Opisthopsis strobe.

So I prematurely upgraded my phone to get a high tech videography tool before I headed to Australia, where I was hosted generously by the Tropical Ecosystems Research Centre of the CSIRO. I also packed a bunch of microscope slides, because I got a great tip from James to use an old-school method to record ant gaits that he picked up from decades-old physiology papers – if you smoke glass with a match, and let insects walk across it, you can record their footsteps. It worked better than I had imagined it would! This project organically evolved into a collaboration where I’d get to play with the ants and record the video, and Professor Waters would do the gait analysis, using tools and code that he’d already used for a previous project. (Yet another collaboration that started on twitter!)

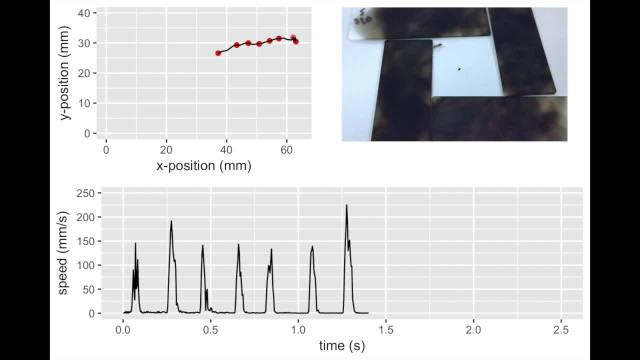

Once I got my lab rig set up, I snatched up some ants (which is harder to do than you might think, because strobing) and brought them into the lab, and voila:

How weird! they’re doing a RUN – STOP – RUN – STOP – RUN – STOP and so on, whenever they’re just moving from point A to point B. That’s what strobing is. Each and every stop, they discretely and firmly tap the ground with the tips of their antennae, then they start their next strobing step once their antennae get lifted to the full and upright position. They’re not jumping — they use what looks like the standard insect tripod gait, but they’re doing it so fast, that at a brief moment, all six legs might be lifted off the surface and moving.

In the video below, you can see their rapid acceleration and deceleration. They’re at rest for double the time that they’re actually moving! Watching the strobe at regular speed, I wouldn’t have guessed this at all. They’re spending more time checking the ground with their antennae than they are moving. And, they clearly are making a solid tap on the surface because their antennae mark the smoked glass as much as their feet do.

opis-tracks-for-web.mp4

I didn’t walk into this work with any particular hypothesis. I first wanted to actually see what strobing was before I tried to develop a clear idea about why they’re doing it! And now that I see what strobing is, well, I’m more boggled. Which is so cool, don’t you love a good mystery? We’ve got a few wacky ideas. The most sensible one is that the ants are running so fast, that their brains can’t keep up with the visual input, so they need to stop so that their brain’s can make sense of the input. This might sound far-fetched, but this is apparently what some extremely fast-running beetles do.

There are some other insects that do the strobe-walk, and one thing they have in common is mighty big eyes. We don’t have a Unified Theory of Strobe Gait, but maybe we’ve done a bit more to inspire folks to work on this. If you’ve got an iPhone, this is something that you can do on your own, too!

Our paper with these results, and more, has just come to press:

Waters, J.S., and T.P. McGlynn 2018. Natural history observations and kinematics of strobing in Australian strobe ants, Opisthopsis haddoni (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Myrmecological News 27: 7-11.

I don’t have any immediate plans to go back to work with strobe ants, though it would be fun.