Natural history is important, but not perceived as an academic job skill

This post is a reflection on a thoughtful post by Jeremy Fox, over on Dynamic Ecology. It encouraged me (and a lot of others, as you see in the comments) to think critically about the laments about the supposed decline of natural history.

I aim to contextualize the core notion of that post. This isn’t a quote, but here in my own words is the gestalt lesson that I took away:

We don’t need to fuss about the decline of natural history, because maybe it’s not even on the decline. Maybe it’s not actually undervalued. Maybe it really is a big part of contemporary ecology after all.

Boy howdy, do I agree with that. And also disagree with that. It depends on what we mean by “value” and “big part.” I think the conversation gets a lot simpler once we agree about the fundamental relationship between natural history and ecology. As the operational definition of the relationship used in the Dynamic Ecology post isn’t workable, I’ll posit a different one.

As a disclaimer, let me explain that I’m not an expert natural historian. Anybody who has been in the field with me is woefully aware of this fact. I know my own critters, but I’m merely okay when it comes to flora and fauna overall. I have been called an entomologist, but if you show me a beetle, there’s a nonzero probability that I won’t be able to tell you its family. There are plenty of birds in my own backyard that I can’t name. Now, with that out of the way:

Let’s make no mistake: natural history is, truly, on the decline. The general public knows less, and cares less, about nature than a few decades ago. Kids are spending more time indoors and are less prone to watch, collect, handle, and learn about plants and creatures. Literacy about nature and biodiversity has declined in concert with a broader decline in scientific literacy in the United States. This is a complex phenomenon, but it’s clear that the youth of today’s America are less engaged in natural history than yesterday’s America.

On the other hand, people love and appreciate natural history as much as they always have. Kids go nuts for any kind of live insect put in front of them, especially when it was just found in their own play area. Adults devour crappy nature documentaries, too. There’s no doubt that people are interested in natural history. They’re just not engaged in it. Just because people like it doesn’t mean that they are doing it or are well informed. That’s enough about natural history and public engagement, now let’s focus on ecologists.

I honestly don’t know if interest in natural history has waned among ecologists. I don’t have enough information to speculate. But this point is moot, because the personal interests of ecologists don’t necessarily have a great bearing on what they publish, and how students are trained.

Natural history is the foundation of ecology. Natural history is the set of facts upon which ecology builds. Ecology is the search to find mechanisms driving the patterns that we observe with natural history. Without natural history, there is no such thing as ecology, just as there is no such thing as a spoken language without words. In the same vein, I once made the following analogy: natural history : ecology :: taxonomy : evolution. The study of evolution depends on a reliable understanding of what our species are on the planet, and how they are related to one another. You really can’t study the evolution of any real-world organism in earnest without having reliable alpha taxonomy. Natural history is important to ecologists in the same way that alpha taxonomy is for evolutionary biologists.

Just as research on evolution in real organisms requires a real understanding of their taxonomy and phylogeny, research in real-world ecology requires a real-world understanding of natural history. (Some taxonomists are often as dejected as advocates for natural history: Taxonomy is on the decline. There is so much unclassified and misclassified biodiversity, but there’s no little funding and even fewer jobs to do the required work. If we are going to make progress in the field of evolutionary biology, then we need to have detailed reconstructions of evolutionary history as a foundation.)

Of course natural history isn’t dead, because if it were, then ecology would not exist. We’d have no facts upon which to base any theories. Natural history isn’t in conflict with ecology, because natural history is the fundamental operational unit of ecology. Natural history comprises the individual bricks of LEGO pieces that ecologists use to build LEGO models.

The germane question is not to ask if natural history is alive or dead. The question is: Is natural history being used to its full potential? Is it valued not just as a product, but as an inherent part of the process of doing ecological research?

LEGO Master Builders know every single individual building element that the company makes. When they are charged with designing a new model, they understand the natural history of LEGO so well that their model is the best model it can be. Likewise, ecologists that know the most about nature are the ones that can build models that best describe how nature works. An ecologist that doesn’t know the pieces that make up nature will have a model that doesn’t look like what it is supposed to represent.

Yes, the best ecological model is the one that is the most parsimonious: an overly complex model is not generalizable. You don’t need to know the natural history of every organism to identify underlying patterns and mechanisms in nature. However, a familiarity with nature to know what can be generalized, and what cannot be generalized, is central to doing good ecology. And that ability is directly tied to knowing nature itself. You can’t think about how generalizable a model is without having an understanding of the organisms and system to which the model could potentially apply.

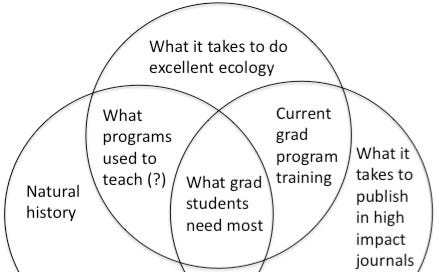

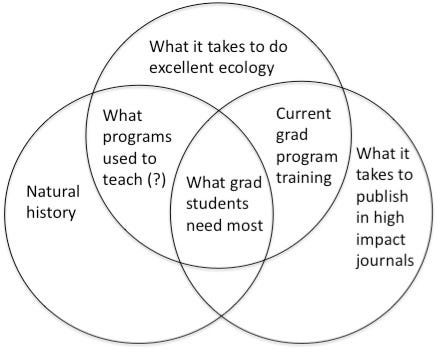

I made an observation a few months back, that graduate school is no longer designed to train excellent scientists, but instead is built to train students how to publish papers. That was a little simplistic, of course. Let me refine that a bit with this Venn diagram:

What’s driving the push to train grad students how to publish? It doesn’t take rocket science to look at the evolutionary arms race for the limited number of academic positions. A record of multiple fancy publications is typically required to get what most graduate advisors regard to be a “good” academic job. If you don’t have those pubs, and you want an academic job, it’s for naught. So graduate programs succeed when students emerge with as their own miniature publication factory.

In terms of career success, it doesn’t really matter what’s in the papers. What matters is the selectivity of the journal that publishes those papers, and how many of them exist. It’s telling that many job search committees ask for a CV, but not for reprints. What matters isn’t what you’ve published, but how much you have and where you’ve published.

So it only makes sense that natural history gets pushed to the side in graduate school. Developing natural history talent is time-intensive, involving long hours in the field, lots of reading in a broad variety of subjects. Foremost, becoming a talented natural historian requires a deliberate focus on information outside your study system. A natural historian knows a lot of stuff about a lot of things. I can tell you a lot about the natural history of litter-nesting ants in the rainforest, but that doesn’t qualify me as a natural historian. Becoming a natural historian requires a deliberate focus on learning about things that are, at first appearance, merely incidental to the topic of one’s dissertation.

Ecology graduate students have many skills to learn, and lots to get done very quickly, if they feel that they’ll be prepared to fend for themselves upon graduation. Who has time for natural history? It’s obvious that ecology grad students love natural history. It’s often the main motivator for going to grad school in the first place. And it’s also just as obvious that many grad students feel a deep need to finish their dissertations with ripe and juicy CVs, and feel that they can’t pause to learn natural history. This is only natural given the structure of the job environment.

Last month I had a bunch of interactions that helped me consider the role of natural history in the profession of ecology. These happened while I was fortunate enough to serve as guest faculty on a graduate field course in tropical biology. This “Fundamentals Course,” run by the Organization for Tropical Studies throughout many sites in in Costa Rica, has been considered to be a historic breeding ground for pioneering ecologists. Graduate students apply for slots in the course, which is a traveling road show throughout many biomes.

I was a grad student on the course, um, almost 20 years ago. I spent a lot of my time playing around with ants, but I also learned about all kinds of plant families, birds, herps, bats, non-ant insects, and a full mess of field methods. And soils, too. I was introduced to many classic coevolved systems, I learned how orchid bees respond to baits, how to mistnet, and I saw firsthand just how idiosyncratic leafcutter ants are in food selection. I came upon a sloth in the middle of its regular, but infrequent, pooping session at the base of a tree. I saw massive flocks of scarlet macaws, and how frog distress calls can bring in the predators of their predators. I also learned a ton about experimental design by running so many experiments with a bunch of brilliant colleagues and mentors, and a lot about communicating by presenting and writing. And I was introduced to new approaches to statistics. And that’s just the start of it the stuff I learned.

I essentially spent a whole summer of grad school on this course. Clearly, it was a transformative experience for me, because now I’m a tropical biologist and nearly all of my work happens at one of the sites that we visited on the course. Not everybody on the course became a tropical biologist, but it’s impossible to avoid learning a ton about nature if you take the course.

The course isn’t that different nowadays. One of the more noticeable things, however, is that fewer grad students are interested, or available, to take the course. I talked to a number of PhD students who wanted to take the course but their advisors steered them away from it because it would take valuable time away from the dissertation. I also talked to an equivalent number of PhD students who really wanted a broad introduction to tropical ecology but were too self-motivated to work on their thesis to make sure that they had a at least few papers out before graduating.

In the past, students would be encouraged to take the course as a part of their training to become an excellent ecologist. Now, students are being dissuaded because it would get in the way of their training to become a successful ecologist.

There was one clear change in the curriculum this year: natural history is no longer included. This wasn’t a surprise, because even though students love natural history, this is no longer an effective draw for the course. When I asked the coordinator why natural history was dropped from the Fundamentals Course, the answer I got had even less varnish than I expected: “Because natural history doesn’t help students get jobs.” And if it doesn’t help them get a job, then they can’t spend too much time doing it in grad school.

Of course we need to prepare grad students for the broad variety of paths they may choose. However, does this mean that something should be pulled from the curriculum because it doesn’t provide a specific transferable job skill? Is the entire purpose of earning a Ph.D. to arm our students for the job market. Is there any room for doing things that make better scientists that are not necessarily valued on the job market?

Are we creating doctors of philosophy, or are we creating highly specialized publication machines?

There are some of grad students (and graduate advisors) who are bucking the trend, and are not shying away from the kind of long-term field experiences that used to be the staple of ecological dissertations. One such person is Kelsey Reider, who among other things is working on frogs that develop in melting Andean glaciers. By no means is she tanking her career by spending years in the field doing research and learning about the natural history of her system. She will emerge from the experience as an even more talented natural historian who, I believe, will have better context and understanding for applying ecological theory to the natural world. Ecology is about patterns, processes and mechanisms in the natural world, right?

Considering that “natural history” is only used as an epithet during the manuscript review process, is natural history valued by the scientific community at all? Most definitely it is! But keep in mind that this value doesn’t matter when it comes to academic employment, funding, high impact journals, career advancement, or graduate training.

People really like and appreciate experts in natural history. Unfortunately, that value isn’t in the currency that is important to the career of an ecologist. And it’d be silly to focus away from your career while you’re in grad school.

But, as Jeremy pointed out in his piece, many of the brilliant ecologists who he knows are also superb natural historians. I suggest that this is not mere coincidence. Perhaps graduate advisors can best serve their students by making sure that their graduate careers include the opportunity for serious training in natural history. It is unwise to focus exclusively on the production of a mountain of pubs that can be sold to high-impact journals.

We should focus on producing the most brilliant, innovative, and broad-minded ecologists, who also publish well. I humbly suggest that this entails a high degree of competency in natural history.