Teaching Tuesday: Incorporating primary literature into courses

As academics, we spend a lot of time reading primary literature (although we often feel it is not enough). It is a real skill to learn to decipher how journal articles are written and how to read them effectively. One barrier is the language and learning a discipline involves learning the language. However, even if you know all the words and concepts, the format of papers is different from most everything else we might read.

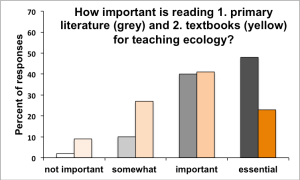

From a survey I did of ecology teachers*: many think that reading primary literature is important in teaching ecology. I included answers for reading textbooks as a comparison. I wasn’t surprised that there was a bit less emphasis on textbook reading but it is obvious still a useful resource for teaching ecology. I certainly also had the impression that reading journal articles was important as an undergraduate but I wasn’t quite sure how to do it.

So if you are using or want to use primary literature in an undergraduate class, how should you go about it? There are perhaps 101 ways to effectively use journal articles as teaching tools. The link is a detailed article which outlines what you can use primary literature for, how to identify good articles, challenges with using primary literature and how to overcome them and finally how to assess learning. There is tons of good advice there, so if you are looking for ways to incorporate the literature but are unsure how, it is a good place to start. Here’s a more personal account of one professor’s approach to integrating the primary literature into a class. I like the idea of building up understanding and directing the students so that their reading is productive.

I found when I was an undergrad, I basically learned how to read primary literature by doing it a lot. My first attempts felt a bit like looking through a fog. I would attend discussion sections where we’d read papers and there were a few students presenting each time. I don’t think I learned anything until I presented a paper myself. Before that, it seemed that every time I missed the main point of the paper.

So when I started running my own section for a writing intensive group of an ecology course as a teaching assistant, I realised I didn’t want my students to be stuck in the rut I had been in. We were to discuss many papers during the semester and I couldn’t wait for the end for all of them to be comfortable. I also didn’t want the focus to be on me (the section was meant to facilitate their independence), so I didn’t want to break down every paper for them. Inspired by discussions in a class about how to teach writing that I was taking, I came up with a simple plan to get students to overcome any issues they might have with discussing primary literature.

The methods were simple**:

Choose recently published papers on topics that students will be able to understand without much background.

Describe the general layout of a paper and how to read it (be brief to give students as much time as possible to read).

Break students into pairs, and have each pair read a different paper for 10-15 minutes.

Allow the pairs to discuss the paper for ~5 minutes.

Give each pair 2-3 minutes to tell the class what the paper was about.

As instructors, we often discuss how to approach reading a paper but we rarely address the intimidation that many students feel when reading scientific writing. Often students get so bogged down in the details of a paper that they can’t see the forest through the trees. So I wanted students to avoid getting caught up in details they didn’t understand (e.g. statistical methods are particularly prone to this). My hope was that I could help students overcome their fears of both reading primary literature and then having something to say about it. I have to admit the first time I tried this I was terrified. I knew that I could briefly read a paper before a discussion and contribute if I needed (sometimes happened more than I’d care to admit as a grad student) but I wasn’t sure how they would do. I wasn’t asking them to describe in detail the paper and I specifically choose papers that were relatively easy to understand the main points. I hoped this was enough. To my relief, it worked!

Student comments on this activity:

“An invaluable skill! Keep encouraging this. Thank you!”

“Was useful because it helped me think about the essential information”

“Speed reading will be a skill I keep-usually I spend so much time I get confused in the readings.”

“Great. Not only familiarized us with various ecological concepts and studies but helped with the ability to skim/read scientific papers for pertinent information.”

“Speed reading was helpful in understanding take away messages from papers—it is a great skill.”

“very useful”, “relevant and important”, “practical”

I was able to describe paper reading very briefly in the beginning of section because my students had all been exposed to reading primary literature in previous courses. If this is the first time your class has seen a journal article, maybe more effort would be needed here. At the end of class I would also take a few moments to point out what they couldn’t pick up from their quick reading. For example, I’d ask some directed questions to the teams about the articles that I was pretty sure that they wouldn’t have picked up on. My goal was to get them to be able to figure out the main story of a paper and realise that they could understand that without knowing all the details. But I didn’t want the take away message to be that fully reading a paper is never necessary. The rest of the semester we discussed many papers and they also needed to read and summarize papers working up to their final proposal so there was many opportunities to teach them about how to read and learn from the literature.

I was lucky because I had small groups of students to work with. I can see ways in which you could modify the activity for larger groups. Maybe having them share what the paper is about in smaller groups rather than the whole class, for example. Mainly I think it is important for them to have to say something about the paper. It is through being forced to quickly summarize the points that students actually learn to ignore all the detailed methodology that they tend to get caught up in. We can tell them to focus on the big picture but most of them (including me as an undergrad) won’t. By not giving the time to get bogged down, they quickly learned to look at the big picture. I was really pleased that both times my students were able to use this experience throughout the course. The discussions were more lively than I’d ever had before as a TA and I did very little talking.

In general, I think incorporating primary literature is important for learning in the sciences. Whether it is exposing students to the papers themselves or their products in an deconstructed way, efforts we make to teach students how to read the scientific literature can only expand their understanding of what science is all about. Now whether they should be able to access the literature after their degree is complete is a whole another debate…

*if you are new to Teaching Tuesdays, I’ve been doing a series of posts that have derived from a survey I distributed broadly to ecology teachers earlier this year. If you are interested in knowing more about what ecology teachers are up to, you can read more here (intro, difficulties, solutions, practice and writing).

**after doing this activity with my students in a couple of courses I remember reading something similar. I think the article was maybe in an ESA newsletter (Eco 101, perhaps) but my cursory searching hasn’t found it. Although I had thought I downloaded it, there is nothing on my hard drive either. If you know of this article, please send me the link! (Update: link, thanks Gary)