What happens when you don’t know anything about the subject you’re teaching?

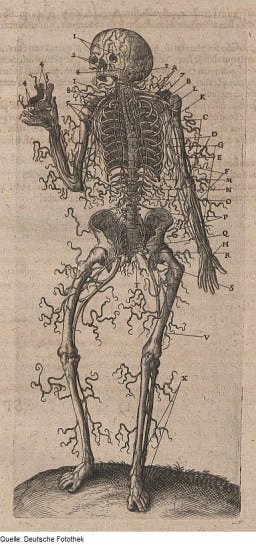

Biologie & Anatomie & Mensch, via Wikimedia commons

Like many grad students in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, I my made a living through grad school as a TA.

One semester, there were open positions in the Human Anatomy cadaver lab. I was foolish enough to allow myself to be assigned to this course. What were my qualifications for teaching an upper-division human anatomy laboratory? I took comparative vertebrate anatomy in college four years earlier. We dissected cats. I barely got a C.

You can imagine what a cadaver lab might be like. The point of the lab was to memorize lots of parts, as well as the parts to which those parts were connected. More happened in lecture, I guess, but in lab nearly the entire grade for students was generated from practical quizzes and exams. These assessments consisted of a series of labeled pins in cadavers.

My job was to work with the students so that they knew all the parts for quizzes and exams. (You might think that memorizing the names of parts is dumb, when you could just look them up in a book. But if you’re getting trained for a career in the health sciences, knowing exactly the names of all these parts and what they are connected to is actually a fundamental part of the job, and not too different from knowing vocabulary as a part of a foreign language.)

The hard part about teaching this class is: once you look inside a human being, we’ve got a helluva lotta parts, all of which have names. I was studying the biogeography of ants. Some of the other grad student TAs spent a huge amount of time prepping, to learn the content that we were teaching each week. Either I didn’t have the time, or didn’t choose to make the time. I also discovered that the odors of the preservatives gave me headaches, even when everything was ventilated properly. Regardless of the excuse that I can invent a posteriori, the bottom line is that I knew far less course material than was expected of the students.

Boy howdy, did I blow it that semester! At the end, my evaluation scores were in the basement. Most of the students thought I sucked. The reason that they thought I sucked is because I sucked. What would you think if you asked your instructor a basic question, like “Is this the Palmaris Longus or the Flexor Carpi Ulnaris?” and your instructor says:

I don’t know? Maybe you should look it up? Let’s figure out what page it is in the book?

The whole point of the lab was for students to learn where all the parts were and what they were called. And I didn’t know how to find the parts and didn’t know the names. I lacked confidence, and my students were far more interested in the subject. It was clear to the students that I didn’t invest the time in doing what was necessary to teach well. They could tell, correctly, that I had higher priorities.

Even though students were in separate lab sections, a big chunk of the grade was based on a single comprehensive practical exam that was administered to all lab sections by the lecture instructor. Even though I taught them all semester – or didn’t teach them at all – their total performance was measured against all other students, including those who were lucky enough to be in other lab sections taught by anatomy groupies. Even I at the time realized that my students drew the short straw.

One of my sections did okay, and was just above the average lab section. The other section – the first of the two – had the best score among all of the lab sections! My students, with the poor excuse of an ignoramus instructor, kicked the butts of all other sections. These are the very same students that gave me the most pathetic evaluation scores of all time. They aced the frickin’ final exam.

What the hell happened?

I inadvertently was using a so-called “best practice” called inquiry-based instruction. That semester, I taught the students nothing, and that’s why they learned.

Now, I know even less human anatomy than I did back then. (I remember the Palmaris Longus, though, because mine is missing.) I bet my students would learn even more now than mine did then, and I also bet that I’d get pretty good evals, to boot. Why is that?

I’d teach the same way I taught back then, but this time around, I’d do it with confidence. If a student asked me to tell the difference between the location of muscle A and muscle B, I’d say:

I don’t know. You should look it up. Find it in the book and let me know when you’ve figured it out.

The only difference between the hypothetical now, and the actual then, is confidence. Of course, there’s no way in heck that I’ll ever be assigned to teach human anatomy again, because the instructors really should have far greater mastery than the students. In this particular lab, I don’t think mastery by the instructor really mattered, as the instructor only needed to tell the students what they needed to know, and the memorization required very little guidance. (For Bloom’s taxonomy people this was all straight-up basic “knowledge.”)

I do not recommend having an ignorant professor teach a course. If a class requires anything more than memorizing a bunch of stuff, then, obviously, the instructor needs to know a lot more than the students. Aside from a laboratory in anatomy, few if any other labs require (or should require) only straight-up memorization of knowledge. Creating the most effective paths for discovery requires an intimate knowledge of the material, especially when working with underprepared students.

For contrasting example, when I’ve taught about the diversity, morphology and evolutionary history of animals, I tell my students the same amount of detail that I told my anatomy students back then: nothing. I provide a framework for learning, and it’s their job to sort it out. If a students asks about the differences between an annelid and a nemadote, I refrain from busting into hours of lecture. But I don’t just lead them to specimens and a book. I need to provide additional lines of inquiry that put their question into context. It’s not just memorizing a muscle. In this case, it’s about learning bigger concepts about evolutionary history and how we study attempt to reconstruct the evolutionary trees of life. I ask them to make specific comparisons and I ask leading questions to make sure that they’re considering certain concepts as they conduct their inquiry. That takes expertise and content knowledge on my part.

To answer the non-rhetorical question that is the title of this post, then I guess the answer is: It will be a disaster.

But if you act with confidence and don’t misrepresent your mastery, then it might be possible to get by with not knowing so much and still have your students learn. Then again, if you’re teaching anything other than an anatomy lab that involves only strict memorization, I’d guess that both you and your students are probably up a creek if you don’t know your stuff.

The semester after was the TA for human anatomy, I taught Insect Biology lab. That was better for everybody.