Designing broader impacts for durable influence

If you're going to put in the work, make sure it will last

When you’re doing broader impacts associated with your research, there’s no limit to what you can do. You can be as creative as you want. I think that open endedness is great, but it also gets folks in trouble.

Once folks start thinking too far outside their standard boxes, they might not have the experience, skill, or commitment required to know whether it’s their ideas are good. For example, so many scientists have thought of developing curricula for middle schools or high schools that’s built on data or ideas generated by their research projects. But in most cases, the curriculum doesn’t have an actual target audience who we know will make avail of it, and nobody was asking for it, and there’s no expert aligning it to state standards, and it might also cost money, and do they have teachers who they know will use it, and will it actually improve student learning? I’ve seen this done well a couple times, but I’ve seen it proposed badly hundreds of times.

Let’s say you want to connect the general public with insects. It’s not a good idea to create an insect-centered monthly hike series at the local nature center if you’re not a regular at the nature center or if you don’t regularly go hiking. But if you’re an entomologist who likes to knit, then connecting knitters to bugs by creating cool designs and sharing them with others is a home run.

Here is one of the most disastrous cases I’ve seen: About 15 years ago, I saw an exhibit at a museum that was developed as a broader impact of an NSF research award. This exhibit was in a high traffic area, frequented by a huge number of school groups as well as families, and was designed to present the results of a relevant research project in an accessible way that would engage the public on this quite interesting topic. This museum was exactly the kind of place that is deserving of from support from broader impacts, as it’s an underfunded public institution1 to the extent that the curatorial and exhibit staff simply can’t keep up with updating and building new exhibits on a regular basis. They’re barely keeping their heads above water.

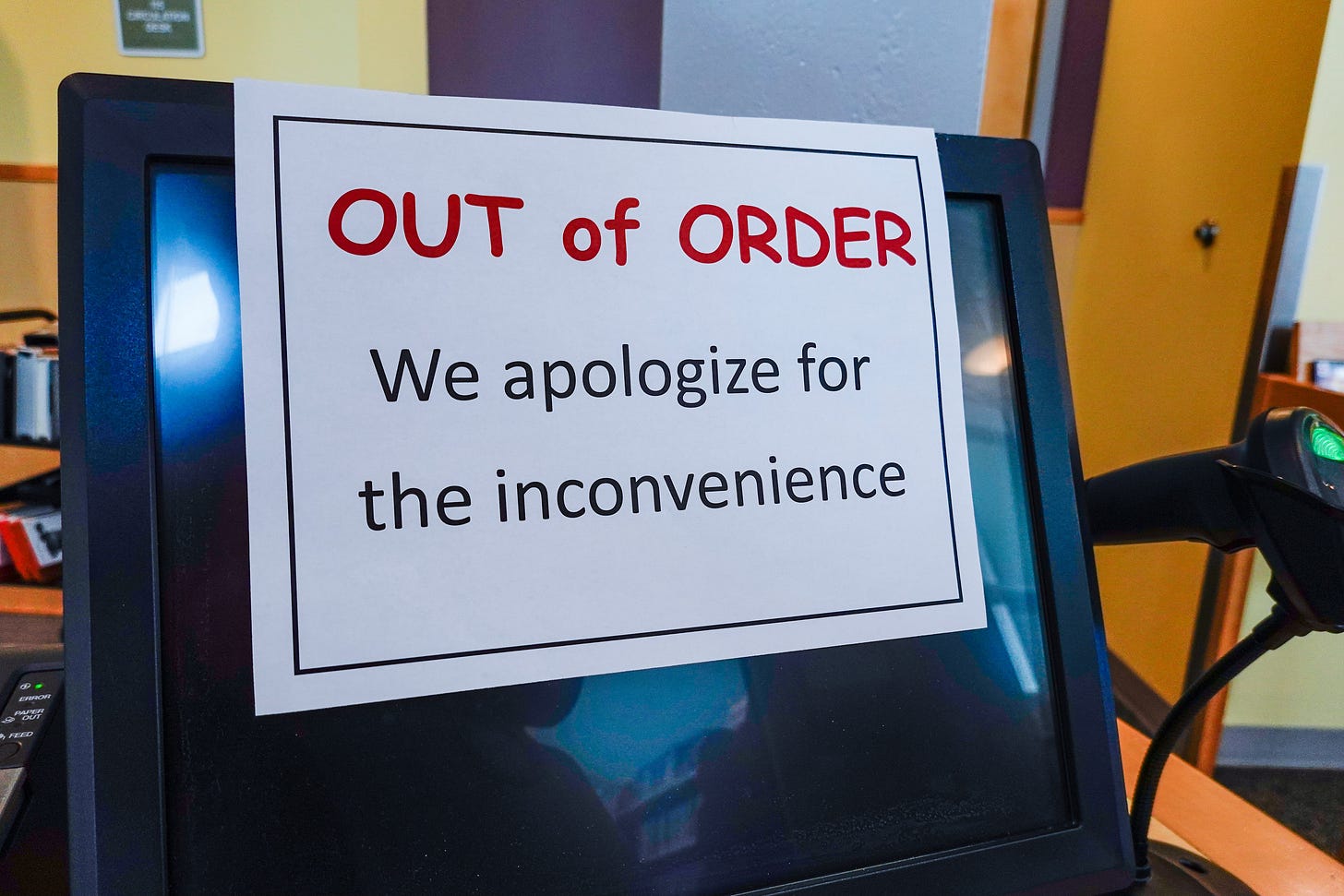

But the exhibit was busted. It had a computerized interface, and some combination of the hardware and software got broken or didn’t survive an update. I don’t know what happened but once the digital piece was broken, in this particular exhibit, the whole thing was useless and uninformative. Just a blank screen with instructions that were moot. It was irreparably kaput, and the looks of the situation prescribed either a full rebuilt or deinstallation. It doesn’t look like it had worked for very long, either.

I visited this museum again a few years ago. The broken exhibit was still there, still broken, and it doesn’t seem like anything had changed over the prior decade. It was still occupying prime space in a hands-on gallery targeting children and families.

Who is responsible for this shortcoming? A bit should go to the folks running the museum, and more should go to the folks responsible for funding the place (because the place is unmistakably underfunded relative to its charge). I think the bulk of the blame has to go to the scientists who built it in the first place. They built an interactive exhibit for a permanent gallery even though it had a brief shelf life and would require periodic maintenance. They handed it over to an institution that didn’t have the resources to keep it going, and it looks like the PI of the project abandoned it just as much.

This should go without saying, but I’ll say it anyway: Don’t do your broader impacts like this, please. Here’s the catch: I think a lot of us wind up doing something like this without even realizing it. We create something that’s designed to have a certain effect, and then we abandon it when we get tired of it, or the money runs out, and the effect might never have really happened.

For example, are you going to start a podcast related to your grant, but what are the odds it’s going to attract a listenership and will people find it once the grant expires and you stopped recording? Are you creating informative videos that ultimately are going to be low-budget recreations of other educational programming that other people are already doing better? Are you building an interpretive sign for a natural area that will fade in the sun in a few years and sit there unreadable and covered with bird poop because there’s nobody to do the upkeep? Did you develop a fancy curriculum that requires lot of supplies or expert support, and once the grant runs out, it stops being used?

I’ve been guilty of something quite similar. In my first tenure-track position, I taught an insect biology course that involved students collecting from a natural city park that was adjacent to the university (almost nobody from campus went down there, oddly enough, even though it’s gorgeous down there). They have a cute little nature center operated by the city. After the city park staff issued our collecting permit for the course, I asked them how I might be of support, and they thought it would be great if I could provide them with a single drawer of insects, arranged as a well-labeled collection cabinet full of identified insects, for the purpose of public display. I gave them what I thought was a gorgeous small collection of insects, all donated by students who had worked at the site. They mounted it for display in a prominent place in the nature center. Though I made one critical error. I didn’t take adequate measures to protect the bugs. It was in a box that could be opened, and even though I told people it should never be opened, surprise, surprise: people opened it. Dermestid beetles got in (which is to be wholly expected). You can protect against this by freezing the collection (or with chemicals), and while I mentioned this issue when I donated it, I should have realized that this information wouldn’t take root. Not long after I donated that collection, I left that university for a new job in a new city. The next year when I was visiting town and swung by the nature center, the box of insects was decimated. Lots of empty pins and dermestid damage everywhere. But still on display, and it was the most sad and pathetic thing. I felt really guilty about this and realized my mistake, but also was no longer in a position to fix it because I no longer had access to the educational collection that I had created and used to develop this exhibit. I understand how these things happen, and what matters isn’t recriminations over having done them poorly before, but making sure that we do them well in the future.

We don’t need to create things that will last forever. It’s okay to run a workshop that serves its audience and is then gone. It’s okay to hold a one-off outreach event if you think it’ll have a positive impact. But it’s a lot better to build relationships that you intend to last, or do things that leverage existing relationships. If you’re trying to serve local tribal communities, you gotta start this by actually knowing and spending time with folks in these communities. If you bumped the person you’re working with at the grocery store, would they know who you are, would you be chatting about your kids soccer team or the new season of What We Do In The Shadows? If not, then that’s where you’ve gotta start. This stuff takes a lot of time. The people stuff is often the most difficult and rewarding part.

Not long ago, I was saying that we need to be able to know how to tell the difference between the stuff that has to be done well, and the things that we can just apply a minimum of effort and then move on. The bottom line here is that we have the choice to phone in our broader impacts, or we can make sure they’re done well. I can accept the possibility that in the case of this museum exhibit, there might have been extenuating circumstances that would have made phoning it in more reasonable than not (for example, if the original PI of the grant had to drop the grant and then someone else picked up the orphaned award; or if someone got sick or experienced a major tragedy or sudden increase in domestic labor; or if it was the idea of a lab member who was excited about it but they left the lab for a cool opportunity on a short timeframe). So I don’t want to judge the person responsible for this particular exhibit. Stuff happens. I do think, however, that this circumstance is emblematic of a broader phenomenon.

So, how do we actually make sure that we do these broader impacts well?

-If you’re developing something that you are expecting to have an effect beyond the life of the grant itself, ground-truth your expectations by talking to experts about the prospect that your work will last or become institutionalized.

-Build on things that you are already doing well.

-Ask yourself, what do you enjoy, and what communities are you already serving? While you might want to find a community that you think is the most disadvantaged to gain your support, if you’re not already reaching out to these folks without the grant, be realistic with yourself about how much effort that you’ll be putting into this community. Helicoptering in with outreach is a waste of everybody’s time.

But what if you don’t yet have those relationships with the people and institutions who you’d like to do the outreach with. Then your broader impacts can be very simple and small activities that are explicitly designed to foster a more productive long-term relationship with people and organizations in populations that you’d like to serve. I don’t think I’ve ever seen in a grant something like, “my department doesn’t have a strong relationship with [community non-profit organization], and conducting these activities with the intention of developing such a relationship is the central purpose of this outreach.” But if I did, I personally would love it, because it shows that the PI gets what it takes to do effective outreach: having relationships with the people you’re working with.

Last thing that has to be said about broader impacts: budget generously. Will it get harmed in panel because too much money is going to the BI? I think almost never. On the other hand, I’ve seen it happen far too often that ambitious broader impacts are underfunded or unfunded, which sends the message that they’re not serious about it or don’t have a realistic understanding of what it will take.

If you thought this was useful, here are a couple more posts that are closely related, which were widely shared when they initially came out:

Broader impacts ≠ reaching underrepresented groups

When the National Science Foundation introduced the required “Broader Impacts” criterion, it took more than a little bit of explaining at the outset.

Broader impacts that have impact

Some while ago, I wrote about experiences serving on NSF panels, just to demystify the experience for folks who haven’t been on panels. I received feedback that this was helpful, so I thought I’d turn some focus on one aspect of review that I think merits additional attention.

I am being vague because I do not want to make this about the particular people or institutions in this example. It’s not about any specific person, but about the broader phenomenon of BI projects being built for the short term and not integrated into our own priorities/institutions/practices/relationships. I don’t live near this museum at all and have have any affiliation with it, to be clear. I just happened to be positioned to know a little more about the place because of conversations I’ve had with people in the museum world, that’s all.

This was enlightening and great examples of poor public administration management. I’ve worked for government a long time and have volunteered for years for museums… no excuse for leaving these things on display. It doesn’t cost anything to take it down and put it in storage.